” It’s a blunt line, almost awkward, and yet it’s the sentence you hear whispered across Northern Ireland right now. Around a thousand people here have taken a step that turns endings into beginnings: pledging their body to science.

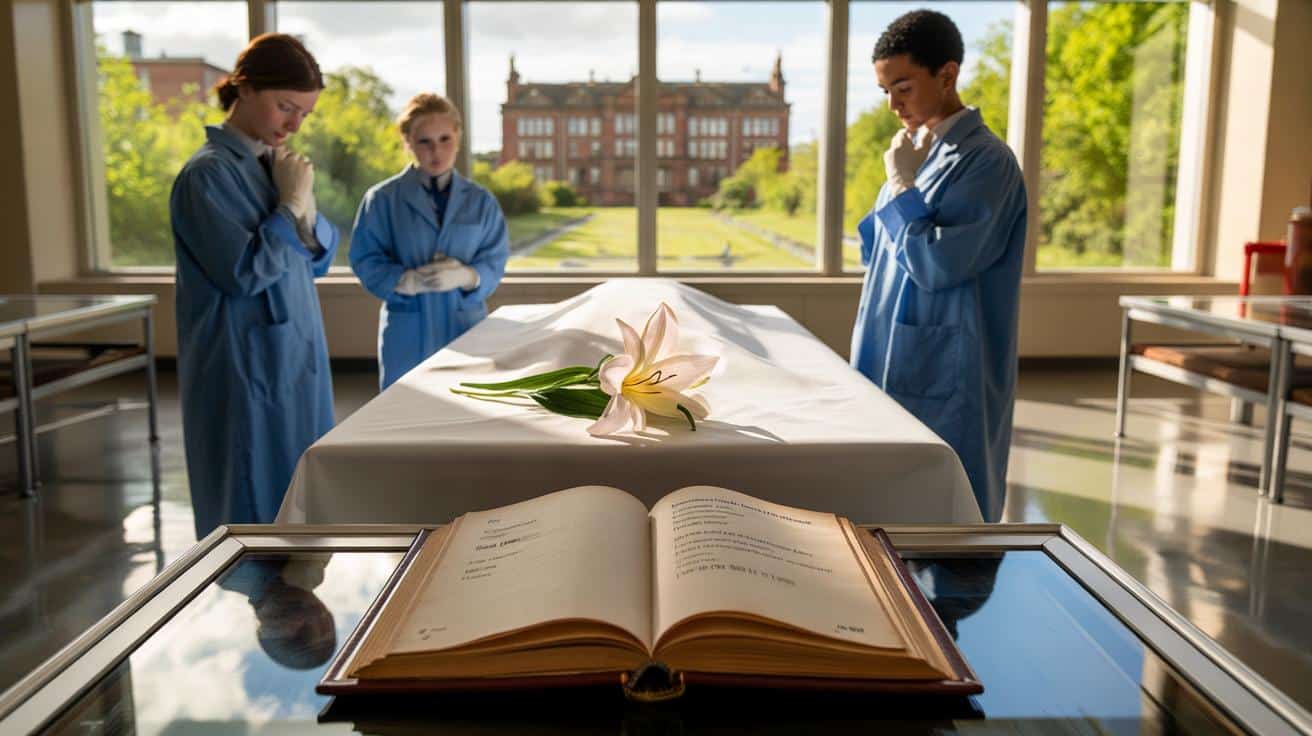

The lift doors open onto a bright corridor at Queen’s University Belfast, and the first thing you notice is the hush. Not silence, exactly — more like attention. Students in blue gowns step carefully, voices low, names remembered. In a glass case sits a book of thanks, pages softened by fingertips, each entry describing a stranger as a teacher.

We’ve all had that moment when a late-night conversation drifts to what happens after we go. That theoretical chat is becoming a practical decision. In Northern Ireland, more people are choosing legacy over ceremony. A simple choice with complicated feelings. One detail sticks.

Why so many in Northern Ireland are saying yes

Body donation here isn’t only about medicine; it’s a form of neighbourliness. People talk about helping the next generation of doctors the way they talk about lending a ladder. There’s grit to it, and warmth, and a streak of independence that says: make something of me.

Ask around and you’ll hear the same refrain: cost, care, and clarity. Funerals are expensive, and for some families the university’s offer to handle cremation later is a relief. Others speak about faith — sometimes a quiet faith, sometimes none — and a wish to skip the fuss. It reads like a practical manifesto.

There’s also pride in local education. Queen’s University Belfast is training the people who’ll treat your niece’s asthma and your father’s hip. A donated body becomes a classroom, a map, a mentor. It’s mundane and profound, and in a place that values plain speaking, **a quiet act of rebellion** against fear.

How body donation actually works here

The process begins in life, not death. You contact the Anatomy Office at Queen’s and ask for the consent forms, which under the Human Tissue Act must be completed and witnessed. Keep a copy at home, give one to a family member, and tell your GP. It’s admin with meaning.

There’s a second step people forget: talk to the people who’ll answer the phone when the time comes. Share the number to call, the short timeframe for transfer, the possibility that circumstances might mean a “no” on the day. Let’s be honest: nobody really does this every day. A calm, early chat can make a hard moment gentler.

Even with consent, **not everyone can be accepted**. Infectious disease, certain surgeries, or a death outside the transport area can get in the way. Families are kept informed and, when acceptance is possible, the university takes over care with discretion.

What really happens after you die

When a donation is accepted, the body is brought to the university and prepared with care. Embalming preserves tissue for teaching; the body may be with the department for months or, more often, up to two to three years. At every turn, students are reminded that this is a person, not a specimen.

What follows looks nothing like TV. Anatomy labs in Belfast are tidy, clinical, almost tender. Students learn the architecture of the human body, the differences between textbook and reality, the quiet weight of responsibility. They learn to say thank you out loud.

At the end of the teaching period, there is cremation, often arranged by the university, and ashes are returned to the family if requested. Some families gather later for a memorial. Others prefer a private walk on a familiar beach. Through it all, staff keep a simple promise: transparency and respect.

Stories behind a thousand signatures

“My aunt always said she didn’t want a fuss.” That’s how Mark from Antrim begins, describing a woman who loved quizzes and hated waste. She read an article, rang the number, and filed the paperwork beside the dog’s vaccination record. It felt ordinary. It changed everything.

After her death, Mark says the process was swift and quietly human. The call, the arrival, the calm voice at the other end of the line. Months later, a letter arrived saying students had learned from her heart. He keeps it between cookbooks, as if it were a recipe for courage.

Not every story is as neat. Sometimes the body can’t be accepted. Families speak of mixed disappointment and relief, and then they choose a different goodbye. Even that choice comes from the same place: a wish to do some good with what’s left. *Time is the most human currency.*

Culture, money, and the Northern Irish way

Why here, and why now? Start with economics. The cost of saying goodbye has crept up, and donation can reduce or remove some of that burden. In a cost-of-living squeeze, pragmatism isn’t cold; it’s caring in a different language.

Then there’s belief, which in Northern Ireland is changing shape. People who once would have chosen a traditional burial are picking something less performative and more purposeful. A classroom in place of a cortege. A legacy in place of a line of cars.

There’s also trust in institutions that feels hard-won. The Anatomy team at Queen’s invites questions, offers straight answers, and hosts memorial events that are warm rather than grand. It’s transparency that breeds courage. It’s dignity without ceremony.

Small steps if you’re thinking about it

Start with one concrete action: call the Anatomy Office at Queen’s and ask for the pack. Read it with a cup of tea, then sleep on it. If it still feels right next week, complete the form, photocopy it, and put the details on the fridge where people look in a crisis.

Tell two people: one who loves you, and one who will answer the phone. Give them the number, and a written note that says “body donor” near your ID. Keep expectations real. Eligibility can change on the day. **Talk early** and you lower the temperature for everyone.

Write down what you’d like to happen afterwards — a poem, a song, a seaside scatter, or nothing at all. Keep it short and kind.

“What’s the point in just being in a coffin? I’d rather be useful.”

- Consent must come from you in life; relatives can’t give it later.

- Organ donation of major organs may prevent body donation; corneas can often be taken.

- Distance and timing matter — acceptance depends on safe transport.

- Universities typically arrange cremation and can return ashes on request.

The bigger conversation we’re finally having

Body donation is a mirror we hold up to a culture. Do we want our last act to be about display, or utility, or love disguised as logistics? In Northern Ireland, a thousand people have answered in their own way, with a signature that echoes into lecture halls and clinics and, one day, a family’s good news.

It’s not for everyone. That’s the point. Choice, spoken early, can be a gift in itself, easing the weight on the people you’ll leave behind. The act is simple, the effect is anything but. When students in Belfast learn the curve of a nerve or the stubbornness of scar tissue, they are meeting generosity in its most literal form. And in a small way, they are meeting you.

| Key point | Detail | Interest for readers |

|---|---|---|

| Consent and process | Forms from Queen’s, witnessed consent, clear next-of-kin instructions | Know exactly how to start and what to tell family |

| Eligibility limits | Certain illnesses, surgeries, distance or timing can lead to a “no” | Realistic expectations, fewer surprises at a hard moment |

| After teaching | Cremation arranged; ashes can be returned; memorial options exist | Reassurance about dignity and closure |

FAQ :

- Who manages body donation in Northern Ireland?Queen’s University Belfast runs the Body Donation Programme for medical education under the Human Tissue Act.

- Can I be an organ donor and a body donor?Major organ donation usually prevents whole-body donation, though eye donation is often compatible. Prioritise life-saving organ donation if that’s your wish.

- Will my family pay for anything?Transport and cremation are typically arranged by the university once a body is accepted, though families may choose to fund a separate memorial.

- How long will the university keep the body?Commonly several months to two or three years, depending on teaching needs and preservation.

- What if my body isn’t accepted on the day?Your family can follow your second preference: a funeral, direct cremation, or another plan you’ve written down. Keep a backup note with your forms.